Is farting good for us? Where do farts come from? Why do only some make sounds? And what’s up with the smell? We tackle your questions about the gas we all pass in this episode.

Bonus: Dan Knights, the scientist we spoke to on this episode, is really good at solving Rubik’s Cubes:

And to see Le Petomane in action, check out this (sadly) silent film made by Edison in 1900:

Music in this episode by Adam Selzer.

This episode was originally released on September 30, 2015. Listen to that version here:

Fart smarts: Understanding the gas we pass

by Brains On!Audio Transcript

Download transcript (PDF)

MOLLY BLOOM: Hello, Brains On listeners. We are celebrating the 4th of July with an explosive blast from the past. One of our favorite episodes we've ever made, fart smarts, understanding the gas we pass, and this encore episode includes a brand new honor roll at the end and a fresh moment of where we answer a fascinating listener question. Now, onto the show.

INTERVIEWER 1: You are listening to Brains On, where we're serious about being curious.

INTERVIEWER 2: Disclaimer, this episode acknowledges the existence of intestines, flatulence, and the various noises made by certain lower parts of the human body. Be warned, these things will be discussed in great detail, but also remember, it's OK to laugh. Now, pull my finger and let's start the show.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: Now, Irene, you just heard that announcement, do you know what flatulence is?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: No.

MOLLY BLOOM: No, well, flatulence comes from the Latin word flatus which means a blowing wind. So it literally means breaking wind, which is another way to describe a certain phenomenon

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Oh, so just like passing gas,

MOLLY BLOOM: Or tooting,

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Cutting the cheese,

MOLLY BLOOM: Barking spiders,

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Or coughing.

MOLLY BLOOM: Whatever you call it, we're talking about farts.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: And yes, farts are funny.

MOLLY BLOOM: Of course, they're funny.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: But they're also really important.

MOLLY BLOOM: We're going to find out about what they are and the important things they do for our bodies.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Keep listening.

MOLLY BLOOM: You are listening to Brains On from American Public Media. I'm Molly Bloom and our co-host today is Irene Weinhagen, who's nine years old. Hi, Irene.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Hi, Molly. Today, we're answering questions about the gas we all pass.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: All?

MOLLY BLOOM: Yes, every human farts, in fact, the average human farts at least 15 times a day.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: That's from one cup up to half a gallon of gas each day.

MOLLY BLOOM: Since it is such a common phenomenon, it makes sense that our listeners are curious about it.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Here's the first question we're going to tackle today.

MOLLY BLOOM: It was sent to us by 8-year-old Maggie from Ardmore, Alabama.

- My question is, are farts good for your body and why?

MOLLY BLOOM: The short answer is yes, farts are good for your body.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: The why part of the question though, is where the interesting stuff comes in.

MOLLY BLOOM: You probably suspect already that farting is tied to what we eat and it is, but the gas we pass isn't actually produced by our bodies.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: When you think about digesting food, you probably think about the different body parts that help you do it.

MOLLY BLOOM: Your stomach,

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Your small intestine,

MOLLY BLOOM: Your large intestine.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: But some of the foods that you eat can't be broken down by your body without help.

MOLLY BLOOM: The help comes from trillions of microorganisms that live inside your gut.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: They're called microbes and they're the ones producing the gas that we pass.

MOLLY BLOOM: To find out how these microbes produce that sometimes smelly gas, we're going to the source

[MUSIC PLAYING]

CATHY LENTINE: Welcome back to Cooking with Cathy. We have a very special guest today, Benny Bacteria.

BENNY BACTERIA: Hi Cathy. Thanks for having me.

CATHY LENTINE: Benny, where are you?

BENNY BACTERIA: I'm down here on the counter.

CATHY LENTINE: Oh. Joe, can we use the super duper extreme zoom lens for this segment? Oh, much better. Benny, looking handsome. Oh and it looks like broccoli is on the menu, OK.

BENNY BACTERIA: I'm going to show you how I break down this broccoli here and turn it into energy that my body, and yours, can use.

CATHY LENTINE: Oh, how exciting. Do you want to use my new immersion blender?

BENNY BACTERIA: Nah, I don't need that. But you need me. Your body can't break down complex sugars, fats, proteins, and fibers without me. So take this broccoli here. I break it down into its smallest parts, molecules, and then I'll take these polymer molecules and break them down into even smaller parts called monomers.

CATHY LENTINE: Can't say that I've ever tried a monomer. What's it taste like?

BENNY BACTERIA: To me, it's delicious. It gives me all the energy I need, and some for you too.

CATHY LENTINE: I don't mean to be rude, Benny, but what is that smell?

BENNY BACTERIA: Oh. Excuse me, Cathy. When I break down these molecules, I produce some gas as well. I don't need it so I excrete it.

CATHY LENTINE: But why does it smell like that, kind of like a rotten egg?

BENNY BACTERIA: Oh, that's just the sulfur you're smelling. And broccoli contains sulfur. So when I process it, I produce hydrogen sulfide, which is frankly pretty darn stinky.

CATHY LENTINE: You can say that again.

BENNY BACTERIA: Breaking down other foods, like say cheese, or maybe whole wheat bread, or something that contains high fructose corn syrup, well, those produce different gases that all smell different. And some are completely odorless.

CATHY LENTINE: Ooh. Why couldn't we have done one of those foods?

BENNY BACTERIA: Well, I suppose we could have done other foods like fatty foods and proteins. They don't produce much gas at all. But everybody loves broccoli.

CATHY LENTINE: Jill, can you turn on the fan? Wow, Benny, thank you so much for being here today.

[APPLAUSE]

BENNY BACTERIA: My pleasure, Cathy.

CATHY LENTINE: After a break, I'll show you how to make my famous three bean casserole.

BENNY BACTERIA: Yes.

CATHY LENTINE: Oh. Now Benny, don't you have to run along?

BENNY BACTERIA: Oh yes. Smell you later.

CATHY LENTINE: Really, Jill, we have to do something about this smell.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

IRENE WEINHAGEN: To find out more about these helpful little living things that make digestion possible--

MOLLY BLOOM: --and are responsible for the gas we pass--

IRENE WEINHAGEN: --we talked to Dan Knights from the University of Minnesota.

MOLLY BLOOM: He studies microbes through a combination of biology and computer science.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: I asked him how many microbes live inside of us.

DAN KNIGHTS: There are a lot of organisms living in your gut. There are usually several different species, so different types of bacteria. And if you count up the actual number of cells of bacteria, it's somewhere around 100 trillion. That's enough that if you had, say, like that many dogs living in your house, it would be enough to cover the entire North America. It's actually more cells, there are more bacterial cells in your body, than there are human cells.

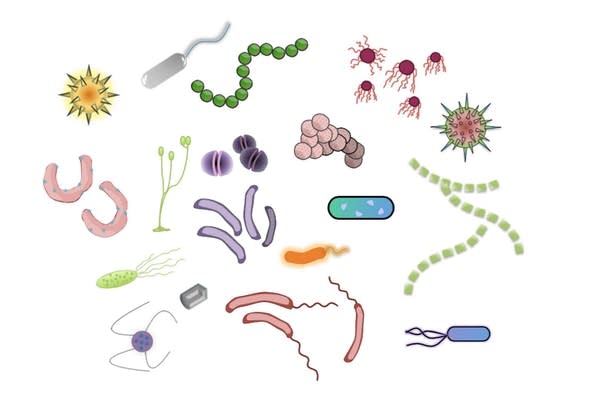

IRENE WEINHAGEN: I was wondering about this. What do they look like?

DAN KNIGHTS: Many of them look like little rods. Some of them have curves in them. Some of them have little tails that they use to spin around. Some are more like little balls and they can attach to each other into a long chain of balls. So there are a lot of different shapes. But many of them look kind of like little tubes.

They're kind of like your pets because you're carrying them around with you everywhere you go. They're not actually bad. Most of them are your friends. And most of them are helping keep you safe from bad bacteria, and they're helping you digest your food.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: What I'm wondering is when they do that, how does that create a fart?

DAN KNIGHTS: The bacteria often produce lots of gases. It just builds up inside you and it has to get out somewhere. And when it comes out, that's what the fart is.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Cool.

MOLLY BLOOM: So remember when I first told you about all the microorganisms in the gut, you were kind of grossed out?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Yes. Yes, I was. Because when you described it, I was imagining tiny little living worms crawling around in my body every day, and that I was, like, gross.

DAN KNIGHTS: There are two things that maybe will make it a little bit less gross. One is that they're actually mostly only in your gut. So they don't get into the other parts of your body like through your blood into your arms and legs and whatnot. And the other is that they're really, really tiny.

So if you think of a piece of poop is about so big. And then think of a piece of corn. A little kernel of corn is probably 1/20 the size, like the poop is 20 or 30 times bigger than the corn. Rice is maybe-- the corn is 10 times bigger than the rice. Then if you look at a grain of salt, the rice is probably 100 times bigger than the grain of salt. And the grain of salt is 600 times bigger than the bacteria. So that's how tiny they are.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Wow.

DAN KNIGHTS: Yeah, they're so tiny that if you look at your fingertip, you can think of the little ridges on your fingertip like roads in a city of bacteria. And there are probably as many bacteria living just on one fingertip as are people living in a small city.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Wow. That does change my opinion about it being so gross.

DAN KNIGHTS: They're really, really tiny. And like I said, most of them are your friends and they're actually supposed to be there. They're also everywhere. They're on every surface in this room. They're all over your skin. Food has some in it. And it's not really a bad thing. You actually want to have lots of bugs in you. And for the most part, you want to have lots of types of bugs.

If you didn't have any bugs living in you, your immune system wouldn't develop properly. Your gut wouldn't actually physically develop all of the right structures in it. And it would make it very easy for you to get infected by a bad bug later on in life if you got exposed.

Your bacteria actually come initially during birth. I mean, the bacteria have to get in there somehow. So they're coming in generally through the mouth, and they're coming in on the food that you're eating, they're coming in on a baby's hands when they touch things and then stick their hands in their mouths.

And we know now that that's actually a really important normal thing that we're really supposed to have all of these bacteria, and it would probably not be a good thing if you kept your baby extra clean all the time and prevented it from getting new bacteria into its tummy.

Bacteria are all over us and all around us and they live inside us and yet we don't really know that much about many of them yet. So it's kind of a new frontier to explore. And I think in a way, because we can study them now using their genes, we're learning more about ourselves and how our own bodies work.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: We're working on a new episode all about animal farts. Turns out a lot of animals fart. We want to hear what you think those farts sound like. Make a recording of your best fart guess. Maybe it's a monkey fart, or a panda, or a salmon. Maybe even a butterfly? Get creative and send your fart recordings to hello@brainson.org.

Sanden and Marc are busy getting their talking points ready for their next debate, which is cooler, deep sea or outer space. But before we hear from them, we want to hear from you. Which of those do you think is cooler, and why? Send us your deep sea or outer space arguments to hello@brainson.org. We'll include some of them in our debate episode.

And when you send us your ideas, you will be added to the Brains Honor Roll. We started it to thank all the amazing kids who share their mystery sounds, drawings, high fives, and questions. Like this one from Jasper in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

JASPER KAVANAGH: Hi. My name is Jasper Kavanagh I am nine years old and from Chapel Hill. My question is, how does the Earth support really heavy buildings like the Empire State Building.

MOLLY BLOOM: We'll answer that question during our Moment of Um and read the most recent group to be added to the brain's honor roll all at the end of the show.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

You're listening to Brains On from American Public Media.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: I'm Irene Weinhagen.

MOLLY BLOOM: And I'm Molly Bloom. Irene, before we go any further, it's time to put your ears to the test with the mystery sound.

GIRL: Mystery sound.

MOLLY BLOOM: worry, it's not a fart.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Aw!

MOLLY BLOOM: Here it is.

[MYSTERY SOUND]

Any guesses?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Maybe like some kind of a truck with animals in it, like, I don't know what kind of animal, but an animal that snorts.

MOLLY BLOOM: You're getting--

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Besides a pig.

MOLLY BLOOM: Yeah, you were getting very close. We'll be back with the answer in just a little bit. Irene, can you play us your mystery sound that you brought with you?

[FART SOUNDS]

So that was Irene's mystery sound that she brought for us. Do you have any guesses, people listening at home? Let's give them a second to think about it before you reveal the answer.

[FART SOUNDS]

OK, what is it?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Our mystery sound is a whoopee cushion.

MOLLY BLOOM: Can you describe what a whoopee cushion is?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: A whoopee cushion is a small bag with a small nozzle which you blow air into and then sit on and it creates a noise like a fart.

MOLLY BLOOM: And what do you use a whoopie cushion for?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: You use a whoopee cushion for pranks, to just be funny, for all sorts of kinds of things, whatever you need a fart sound for but you don't feel like farting.

MOLLY BLOOM: [LAUGHS] Perfect. And that brings us to our next question.

JACK: My name is Jack. I live in Chicago, and I'm seven years old. My question is, why do farts make sound?

MOLLY BLOOM: Good question, Jack. And let's face it, the sound of passing gas is one of its most memorable--

IRENE WEINHAGEN: --and comical--

MOLLY BLOOM: --qualities.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: And like snowflakes, every vote is unique. Some are loud. Some are long. Some are short. And some are silent.

MOLLY BLOOM: Like ninjas, silent but deadly.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Well, not all silent ones are deadly.

MOLLY BLOOM: True. In fact, a lot of silent farts are completely odorless.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: But how does a fart make noise?

MOLLY BLOOM: Here with the answer is producer, Sanden Totten.

SANDEN TOTTEN: Hey, guys. Jack's question might sound a little strange at first, but it's pretty fascinating stuff. Basically, the noise factor has to do with three things. First, volume, or the amount of gas you pass. Second is force. That's how strong the gas is pushed out. And third is the size of the hole the gas rushes through. That hole, of course, is the one we also expel waste from. I'm talking about the hole in our rumps.

I'll explain more about that aspect in a minute. But first, you may have noticed I didn't mention the cheeks of the derriere. A lot of people blame those for the sound of a fart, but in reality, they have very little to do with the noises we make.

MOLLY BLOOM: I guess that makes sense. I've heard dogs fart and their butts are definitely not built the same way as ours.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: No cheeks on a dog.

SANDEN TOTTEN: Right. So back to where the noise comes from. I mentioned it has a lot to do with the end of your digestive tract, that opening in your rear end. When a lot of gas is pushed out of that tiny opening in short order, it vibrates the tissue. As we learned in our music episode, check it out if you haven't, vibrations create sound waves, and in this case, when the opening of your bum vibrates, it goes [FART SOUND].

IRENE WEINHAGEN: But what makes some farts so loud and others so quiet? And what about the silent ones?

SANDEN TOTTEN: OK, for that, I'm going to need some help. So I've asked a tuba to join me. Welcome, tuba.

[TUBA PLAYING]

Now musicians may not want to hear this, but farting is not too different from playing a brass instrument. Let us demonstrate. To make a sound, you have to press your lips tightly together and blow air through the opening of the instrument. Tuba, please.

[TUBA PLAYING]

Now let's try to blow the same amount of air through the opening with super tight lips. Go ahead, tuba.

[TUBA PLAYING]

Of course, sometimes we pass just a little gas. So what does it sound like when you squeeze just a little air through tightly pressed lips.

[TUBA PLAYING]

Sometimes you try to let that gas out slowly, as tuba here is demonstrating.

[TUBA PLAYING]

But then you decide to push it all out fast just to speed things up. Sometimes, we're more relaxed. So tuba, what does it sound like when your lips are more relaxed.

[TUBA PLAYING]

And if your lips are really relaxed.

[TUBA PLAYING]

Pretty much silent. So as you can hear, you can really get a lot of different sounds by varying things like the amount of air, the force that air is pushed out, and the size of the opening that air is pushed through.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Wow. Who knew our butts were so musically inclined? Far too kind of like mini performances.

SANDEN TOTTEN: Yeah. And you know, some people have actually made good money playing that bodily instrument. In the late 1800s, there was a gentleman in France named Joseph Pujol, and his stage name, I kid you not, was Le Pétomane, which roughly means fartomaniac.

MOLLY BLOOM: What? That cannot be real.

SANDEN TOTTEN: Seriously. He was famous for being able to control his farts. He would put on shows at the legendary Moulin Rouge cabaret in Paris where he'd do impressions. Here's a clip from a movie about his life. It's called Le Pétomeane. Here he's played by an English actor, but it'll give you a sense of what he did.

JOSEPH PUJOL: First, I give you the tenor voice. [FARTS] The bass. [FARTS] The soprano. [FARTS]

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Wow. How did he do it? Lots and lots of beans.

SANDEN TOTTEN: Actually, he learned to suck air into the opening of his behind and let it out at will. And he never had to worry about leaving his instrument at home, it was always with him. And he never had to schlep around a tuba everywhere.

[TUBA PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: Thanks for the explanation, Sanden.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: See ya.

[TUBA PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: Let's go back to that mystery sound. Here it is again, and this time with a little clue.

[MYSTERY SOUND]

So what is your guess now?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Pretty much I still don't know, but I'm thinking it's still some kind of a truck or something going down the street with some kind of an animal inside.

MOLLY BLOOM: Here with the answer is Brittany Shanka. She studies animal science at the University of Minnesota.

BRITTANY SHANKA: The sound that you're hearing is a cow chewing her cud. She'll eat first, and then she'll swallow that food, and that will go into the first compartment of her stomach. And then eventually, she'll spit that food back up and chew it up better and then swallow it so it goes into the other compartments of the stomach so it can be further digested.

MOLLY BLOOM: And what does that have to do with passing gas?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: I think what it does is because it's eating the food and then it goes into the compartment and then it just backs up and then eats it again and then that kind of has to do with the microbes.

MOLLY BLOOM: Mm-hmm.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Because then when it food backs up and eats it again, soon afterwards, it's going to be a fart.

[MOLLY LAUGHS]

A cow fart.

MOLLY BLOOM: To tell us is producer Marc Sanchez.

MARC SANCHEZ: Irene's guess is right on the money. Cows have microbes in their guts too. But their digestion works differently than ours. The gas cows pass is mostly in the form of methane. But what a lot of people don't know is how they let it out. About 93% of methane from cows is released through their mouths, not their backsides.

[COW MOOING]

Cows are part of a class of mammals called ruminants. Goats, sheep, bison, they're all ruminants too. And the thing that makes these animals alike is the part of their stomachs called the rumen. Some of you may have heard that cows have four stomachs. Technically, that's not true. Cows, like all ruminants, have one stomach with four compartments, or chambers. The rumen is the first chamber. And that's where all the gas comes from, through a process called fermentation.

When a cow eats, say, a big helping of grass or corn, there's hardly any chewing that goes on. They pretty much swallow everything whole. From there, it's off to the rumen. And that's where the microbes start to feast. This is what sets off fermentation. The leftovers of what the microbes don't use come out in the form of methane. I talked to Ermias Kebreab. He's a professor at UC Davis, and he studies cows and methane. And he broke down how cows break down their food.

ERMIAS KEBREAB: If you look at grass, they have cellulose. Cellulose is basically sugar or starch that's sort of joined together, and they have strong bonds that the microbes can attack and break down. They use that to grow themselves. So when they are breaking it down and using it to build their own bodies, they produce hydrogen.

MARC SANCHEZ: There are other types of microbes in the room and that feed off hydrogen. Those are called methanogens. And it's these methanogen microbes that give off, you guessed it, methane.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

A cow can't break down and ferment all its food at once. So what happens next might seem a little gross to you and me, but they sort of burp up a little ball of food called cud. Do you remember the mystery sound? That was a cow bringing her cud back into her mouth and chewing it up again.

That's what they do. And that's also how she releases the methane built up in her rumen. Several chews later, she swallows and sends her cud back down, and the microbes start the whole process again. This happens over and over until all the nutrients from that cud have been absorbed.

A healthy cow is pretty much constantly producing methane and releasing it into the atmosphere. And it turns out, all that methane can be problematic. Just like carbon dioxide and water vapor, methane is a greenhouse gas. Basically, a gas that can trap heat. You may have heard that excess greenhouse gases are contributing to climate change and heating up the Earth too quickly. But they're not all bad. We need greenhouse gases in moderation to stay warm.

ERMIAS KEBREAB: Without greenhouse gases, we won't be able to survive on Earth. Because the average temperature of Earth would be -18 degrees Centigrade if there was no greenhouse gas effect.

MARC SANCHEZ: For those of you playing in the US, that's just below 0 degrees Fahrenheit. Pretty chilly. But with all the cows and goats and cars and coal burning factories we rely on, we're producing too many greenhouse gases. Ermias is trying to figure out how to cut down the amount of methane cows give off. One way to do that is to change their diets,

ERMIAS KEBREAB: If you provide animals with easily degradable, less fibrous materials, then you would reduce the amount of methane that's produced as well. Very, very recently, there has been a development where a company has come up with a compound that would inhibit the production of methane, and they have shown that they can reduce it by about 30%.

MARC SANCHEZ: A 30% reduction in methane could be a huge breakthrough when it comes to cutting back the amount of greenhouse gases that are warming up the Earth. But like Ermias said, this is a brand new discovery, and there will need to be a lot of testing before this idea could have any major impact. Luckily, the farts that we humans produce are not a major contributor to the amount of greenhouse gases.

[COW MOOING]

So go ahead, enjoy those beans and broccoli.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Thanks, Marc.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Everyone passes gas.

MOLLY BLOOM: The gas is produced by the trillions of microbes living in our guts.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: And without these microorganisms, we wouldn't be able to digest food. And when we fart, it's actually the gas we're letting out.

MOLLY BLOOM: The smell of the gas the microbes produce depends on what we eat.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: And the sound the gas makes when it comes out is controlled by our bodies.

MOLLY BLOOM: Before we wrap up this episode, it's time to answer this question from Jasper.

JASPER KAVANAGH: Hi. My name is Jasper Kavanagh. I am nine years old, and from Chapel Hill. My question is, how does the Earth support really heavy buildings like the Empire State Building.

MOLLY BLOOM: It's time for our Moment of Um.

SUBJECTS: Um.

RONADH COX: The crust of the Earth is actually very thick. It's about 20 miles thick. My name is Ronadh Cox, and I'm a professor of geosciences at Williams College. If you imagine that the Earth is like an orange-- So you know when you hold an orange, it's got all the little lumpy bits on the skin? The mountain ranges on the surface of the Earth would be smaller than the lumps on the skin of the orange. So the Empire State Building looks really big to us and it looks really heavy, but compared to how big the Earth is and compared to how thick the crust of the Earth is, it's really not very big at all, and so the Earth doesn't even notice that it's there.

But of course, if you go to a place where you're not actually building on the bedrock of the Earth's crust but you are putting your building up on soft sediments, like dirt, mud, sand, then your building could sink into it. But it wouldn't be sinking into the crust, it would be sinking into the soft goo. It would be like instead of making a LEGO castle on a table, if you went and tried to build a LEGO castle on a soupy, gooey, swampy tub of mud, and the LEGO castle would sink into that. And that's why the Leaning Tower of Pisa is leaning, because it's not on solid rock and the ground that it was built on is settling underneath it.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: While you contemplate the bumps on the nearest orange, I'm going to hand out virtual high fives to the most recent group of kids to be added to the Brains Honor Roll.

[LISTING HONOR ROLL]

INTERVIEWER 3: (SINGING) Brains Honor Roll [INAUDIBLE]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: That's it for this episode of Brains On.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: This episode was produced by Marc Sanchez, Sanden Totten, and Molly Bloom.

MOLLY BLOOM: Many thanks to Michael Sadowski, Laura Zabel, Levi Weinhagen, Sunpri Cower of UC Davis, Justin Sewell of UC San Francisco, Glenn R. Gibson of the University of Reading, James Buxbum of the University of Southern California, Evan Clark, Doug Rowe, Eric Wrangham, and Joe [? Feigs. ?]

IRENE WEINHAGEN: You can listen to past episodes at our website, brainson.org.

MOLLY BLOOM: Or in your favorite podcast app.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: You can find us on Instagram and Twitter.

MOLLY BLOOM: We're @Brains_On.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: And we're on Facebook too.

MOLLY BLOOM: And you can email us anytime at brainson at m, as in Minnesota, pr.org.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Thanks for listening.

[FART SOUNDS]

INTERVIEWER 1: You are listening to Brains On, where we're serious about being curious.

INTERVIEWER 2: Disclaimer, this episode acknowledges the existence of intestines, flatulence, and the various noises made by certain lower parts of the human body. Be warned, these things will be discussed in great detail, but also remember, it's OK to laugh. Now, pull my finger and let's start the show.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: Now, Irene, you just heard that announcement, do you know what flatulence is?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: No.

MOLLY BLOOM: No, well, flatulence comes from the Latin word flatus which means a blowing wind. So it literally means breaking wind, which is another way to describe a certain phenomenon

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Oh, so just like passing gas,

MOLLY BLOOM: Or tooting,

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Cutting the cheese,

MOLLY BLOOM: Barking spiders,

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Or coughing.

MOLLY BLOOM: Whatever you call it, we're talking about farts.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: And yes, farts are funny.

MOLLY BLOOM: Of course, they're funny.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: But they're also really important.

MOLLY BLOOM: We're going to find out about what they are and the important things they do for our bodies.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Keep listening.

MOLLY BLOOM: You are listening to Brains On from American Public Media. I'm Molly Bloom and our co-host today is Irene Weinhagen, who's nine years old. Hi, Irene.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Hi, Molly. Today, we're answering questions about the gas we all pass.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: All?

MOLLY BLOOM: Yes, every human farts, in fact, the average human farts at least 15 times a day.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: That's from one cup up to half a gallon of gas each day.

MOLLY BLOOM: Since it is such a common phenomenon, it makes sense that our listeners are curious about it.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Here's the first question we're going to tackle today.

MOLLY BLOOM: It was sent to us by 8-year-old Maggie from Ardmore, Alabama.

- My question is, are farts good for your body and why?

MOLLY BLOOM: The short answer is yes, farts are good for your body.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: The why part of the question though, is where the interesting stuff comes in.

MOLLY BLOOM: You probably suspect already that farting is tied to what we eat and it is, but the gas we pass isn't actually produced by our bodies.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: When you think about digesting food, you probably think about the different body parts that help you do it.

MOLLY BLOOM: Your stomach,

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Your small intestine,

MOLLY BLOOM: Your large intestine.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: But some of the foods that you eat can't be broken down by your body without help.

MOLLY BLOOM: The help comes from trillions of microorganisms that live inside your gut.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: They're called microbes and they're the ones producing the gas that we pass.

MOLLY BLOOM: To find out how these microbes produce that sometimes smelly gas, we're going to the source

[MUSIC PLAYING]

CATHY LENTINE: Welcome back to Cooking with Cathy. We have a very special guest today, Benny Bacteria.

BENNY BACTERIA: Hi Cathy. Thanks for having me.

CATHY LENTINE: Benny, where are you?

BENNY BACTERIA: I'm down here on the counter.

CATHY LENTINE: Oh. Joe, can we use the super duper extreme zoom lens for this segment? Oh, much better. Benny, looking handsome. Oh and it looks like broccoli is on the menu, OK.

BENNY BACTERIA: I'm going to show you how I break down this broccoli here and turn it into energy that my body, and yours, can use.

CATHY LENTINE: Oh, how exciting. Do you want to use my new immersion blender?

BENNY BACTERIA: Nah, I don't need that. But you need me. Your body can't break down complex sugars, fats, proteins, and fibers without me. So take this broccoli here. I break it down into its smallest parts, molecules, and then I'll take these polymer molecules and break them down into even smaller parts called monomers.

CATHY LENTINE: Can't say that I've ever tried a monomer. What's it taste like?

BENNY BACTERIA: To me, it's delicious. It gives me all the energy I need, and some for you too.

CATHY LENTINE: I don't mean to be rude, Benny, but what is that smell?

BENNY BACTERIA: Oh. Excuse me, Cathy. When I break down these molecules, I produce some gas as well. I don't need it so I excrete it.

CATHY LENTINE: But why does it smell like that, kind of like a rotten egg?

BENNY BACTERIA: Oh, that's just the sulfur you're smelling. And broccoli contains sulfur. So when I process it, I produce hydrogen sulfide, which is frankly pretty darn stinky.

CATHY LENTINE: You can say that again.

BENNY BACTERIA: Breaking down other foods, like say cheese, or maybe whole wheat bread, or something that contains high fructose corn syrup, well, those produce different gases that all smell different. And some are completely odorless.

CATHY LENTINE: Ooh. Why couldn't we have done one of those foods?

BENNY BACTERIA: Well, I suppose we could have done other foods like fatty foods and proteins. They don't produce much gas at all. But everybody loves broccoli.

CATHY LENTINE: Jill, can you turn on the fan? Wow, Benny, thank you so much for being here today.

[APPLAUSE]

BENNY BACTERIA: My pleasure, Cathy.

CATHY LENTINE: After a break, I'll show you how to make my famous three bean casserole.

BENNY BACTERIA: Yes.

CATHY LENTINE: Oh. Now Benny, don't you have to run along?

BENNY BACTERIA: Oh yes. Smell you later.

CATHY LENTINE: Really, Jill, we have to do something about this smell.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

IRENE WEINHAGEN: To find out more about these helpful little living things that make digestion possible--

MOLLY BLOOM: --and are responsible for the gas we pass--

IRENE WEINHAGEN: --we talked to Dan Knights from the University of Minnesota.

MOLLY BLOOM: He studies microbes through a combination of biology and computer science.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: I asked him how many microbes live inside of us.

DAN KNIGHTS: There are a lot of organisms living in your gut. There are usually several different species, so different types of bacteria. And if you count up the actual number of cells of bacteria, it's somewhere around 100 trillion. That's enough that if you had, say, like that many dogs living in your house, it would be enough to cover the entire North America. It's actually more cells, there are more bacterial cells in your body, than there are human cells.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: I was wondering about this. What do they look like?

DAN KNIGHTS: Many of them look like little rods. Some of them have curves in them. Some of them have little tails that they use to spin around. Some are more like little balls and they can attach to each other into a long chain of balls. So there are a lot of different shapes. But many of them look kind of like little tubes.

They're kind of like your pets because you're carrying them around with you everywhere you go. They're not actually bad. Most of them are your friends. And most of them are helping keep you safe from bad bacteria, and they're helping you digest your food.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: What I'm wondering is when they do that, how does that create a fart?

DAN KNIGHTS: The bacteria often produce lots of gases. It just builds up inside you and it has to get out somewhere. And when it comes out, that's what the fart is.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Cool.

MOLLY BLOOM: So remember when I first told you about all the microorganisms in the gut, you were kind of grossed out?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Yes. Yes, I was. Because when you described it, I was imagining tiny little living worms crawling around in my body every day, and that I was, like, gross.

DAN KNIGHTS: There are two things that maybe will make it a little bit less gross. One is that they're actually mostly only in your gut. So they don't get into the other parts of your body like through your blood into your arms and legs and whatnot. And the other is that they're really, really tiny.

So if you think of a piece of poop is about so big. And then think of a piece of corn. A little kernel of corn is probably 1/20 the size, like the poop is 20 or 30 times bigger than the corn. Rice is maybe-- the corn is 10 times bigger than the rice. Then if you look at a grain of salt, the rice is probably 100 times bigger than the grain of salt. And the grain of salt is 600 times bigger than the bacteria. So that's how tiny they are.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Wow.

DAN KNIGHTS: Yeah, they're so tiny that if you look at your fingertip, you can think of the little ridges on your fingertip like roads in a city of bacteria. And there are probably as many bacteria living just on one fingertip as are people living in a small city.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Wow. That does change my opinion about it being so gross.

DAN KNIGHTS: They're really, really tiny. And like I said, most of them are your friends and they're actually supposed to be there. They're also everywhere. They're on every surface in this room. They're all over your skin. Food has some in it. And it's not really a bad thing. You actually want to have lots of bugs in you. And for the most part, you want to have lots of types of bugs.

If you didn't have any bugs living in you, your immune system wouldn't develop properly. Your gut wouldn't actually physically develop all of the right structures in it. And it would make it very easy for you to get infected by a bad bug later on in life if you got exposed.

Your bacteria actually come initially during birth. I mean, the bacteria have to get in there somehow. So they're coming in generally through the mouth, and they're coming in on the food that you're eating, they're coming in on a baby's hands when they touch things and then stick their hands in their mouths.

And we know now that that's actually a really important normal thing that we're really supposed to have all of these bacteria, and it would probably not be a good thing if you kept your baby extra clean all the time and prevented it from getting new bacteria into its tummy.

Bacteria are all over us and all around us and they live inside us and yet we don't really know that much about many of them yet. So it's kind of a new frontier to explore. And I think in a way, because we can study them now using their genes, we're learning more about ourselves and how our own bodies work.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: We're working on a new episode all about animal farts. Turns out a lot of animals fart. We want to hear what you think those farts sound like. Make a recording of your best fart guess. Maybe it's a monkey fart, or a panda, or a salmon. Maybe even a butterfly? Get creative and send your fart recordings to hello@brainson.org.

Sanden and Marc are busy getting their talking points ready for their next debate, which is cooler, deep sea or outer space. But before we hear from them, we want to hear from you. Which of those do you think is cooler, and why? Send us your deep sea or outer space arguments to hello@brainson.org. We'll include some of them in our debate episode.

And when you send us your ideas, you will be added to the Brains Honor Roll. We started it to thank all the amazing kids who share their mystery sounds, drawings, high fives, and questions. Like this one from Jasper in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

JASPER KAVANAGH: Hi. My name is Jasper Kavanagh I am nine years old and from Chapel Hill. My question is, how does the Earth support really heavy buildings like the Empire State Building.

MOLLY BLOOM: We'll answer that question during our Moment of Um and read the most recent group to be added to the brain's honor roll all at the end of the show.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

You're listening to Brains On from American Public Media.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: I'm Irene Weinhagen.

MOLLY BLOOM: And I'm Molly Bloom. Irene, before we go any further, it's time to put your ears to the test with the mystery sound.

GIRL: Mystery sound.

MOLLY BLOOM: worry, it's not a fart.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Aw!

MOLLY BLOOM: Here it is.

[MYSTERY SOUND]

Any guesses?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Maybe like some kind of a truck with animals in it, like, I don't know what kind of animal, but an animal that snorts.

MOLLY BLOOM: You're getting--

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Besides a pig.

MOLLY BLOOM: Yeah, you were getting very close. We'll be back with the answer in just a little bit. Irene, can you play us your mystery sound that you brought with you?

[FART SOUNDS]

So that was Irene's mystery sound that she brought for us. Do you have any guesses, people listening at home? Let's give them a second to think about it before you reveal the answer.

[FART SOUNDS]

OK, what is it?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Our mystery sound is a whoopee cushion.

MOLLY BLOOM: Can you describe what a whoopee cushion is?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: A whoopee cushion is a small bag with a small nozzle which you blow air into and then sit on and it creates a noise like a fart.

MOLLY BLOOM: And what do you use a whoopie cushion for?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: You use a whoopee cushion for pranks, to just be funny, for all sorts of kinds of things, whatever you need a fart sound for but you don't feel like farting.

MOLLY BLOOM: [LAUGHS] Perfect. And that brings us to our next question.

JACK: My name is Jack. I live in Chicago, and I'm seven years old. My question is, why do farts make sound?

MOLLY BLOOM: Good question, Jack. And let's face it, the sound of passing gas is one of its most memorable--

IRENE WEINHAGEN: --and comical--

MOLLY BLOOM: --qualities.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: And like snowflakes, every vote is unique. Some are loud. Some are long. Some are short. And some are silent.

MOLLY BLOOM: Like ninjas, silent but deadly.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Well, not all silent ones are deadly.

MOLLY BLOOM: True. In fact, a lot of silent farts are completely odorless.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: But how does a fart make noise?

MOLLY BLOOM: Here with the answer is producer, Sanden Totten.

SANDEN TOTTEN: Hey, guys. Jack's question might sound a little strange at first, but it's pretty fascinating stuff. Basically, the noise factor has to do with three things. First, volume, or the amount of gas you pass. Second is force. That's how strong the gas is pushed out. And third is the size of the hole the gas rushes through. That hole, of course, is the one we also expel waste from. I'm talking about the hole in our rumps.

I'll explain more about that aspect in a minute. But first, you may have noticed I didn't mention the cheeks of the derriere. A lot of people blame those for the sound of a fart, but in reality, they have very little to do with the noises we make.

MOLLY BLOOM: I guess that makes sense. I've heard dogs fart and their butts are definitely not built the same way as ours.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: No cheeks on a dog.

SANDEN TOTTEN: Right. So back to where the noise comes from. I mentioned it has a lot to do with the end of your digestive tract, that opening in your rear end. When a lot of gas is pushed out of that tiny opening in short order, it vibrates the tissue. As we learned in our music episode, check it out if you haven't, vibrations create sound waves, and in this case, when the opening of your bum vibrates, it goes [FART SOUND].

IRENE WEINHAGEN: But what makes some farts so loud and others so quiet? And what about the silent ones?

SANDEN TOTTEN: OK, for that, I'm going to need some help. So I've asked a tuba to join me. Welcome, tuba.

[TUBA PLAYING]

Now musicians may not want to hear this, but farting is not too different from playing a brass instrument. Let us demonstrate. To make a sound, you have to press your lips tightly together and blow air through the opening of the instrument. Tuba, please.

[TUBA PLAYING]

Now let's try to blow the same amount of air through the opening with super tight lips. Go ahead, tuba.

[TUBA PLAYING]

Of course, sometimes we pass just a little gas. So what does it sound like when you squeeze just a little air through tightly pressed lips.

[TUBA PLAYING]

Sometimes you try to let that gas out slowly, as tuba here is demonstrating.

[TUBA PLAYING]

But then you decide to push it all out fast just to speed things up. Sometimes, we're more relaxed. So tuba, what does it sound like when your lips are more relaxed.

[TUBA PLAYING]

And if your lips are really relaxed.

[TUBA PLAYING]

Pretty much silent. So as you can hear, you can really get a lot of different sounds by varying things like the amount of air, the force that air is pushed out, and the size of the opening that air is pushed through.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Wow. Who knew our butts were so musically inclined? Far too kind of like mini performances.

SANDEN TOTTEN: Yeah. And you know, some people have actually made good money playing that bodily instrument. In the late 1800s, there was a gentleman in France named Joseph Pujol, and his stage name, I kid you not, was Le Pétomane, which roughly means fartomaniac.

MOLLY BLOOM: What? That cannot be real.

SANDEN TOTTEN: Seriously. He was famous for being able to control his farts. He would put on shows at the legendary Moulin Rouge cabaret in Paris where he'd do impressions. Here's a clip from a movie about his life. It's called Le Pétomeane. Here he's played by an English actor, but it'll give you a sense of what he did.

JOSEPH PUJOL: First, I give you the tenor voice. [FARTS] The bass. [FARTS] The soprano. [FARTS]

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Wow. How did he do it? Lots and lots of beans.

SANDEN TOTTEN: Actually, he learned to suck air into the opening of his behind and let it out at will. And he never had to worry about leaving his instrument at home, it was always with him. And he never had to schlep around a tuba everywhere.

[TUBA PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: Thanks for the explanation, Sanden.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: See ya.

[TUBA PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: Let's go back to that mystery sound. Here it is again, and this time with a little clue.

[MYSTERY SOUND]

So what is your guess now?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Pretty much I still don't know, but I'm thinking it's still some kind of a truck or something going down the street with some kind of an animal inside.

MOLLY BLOOM: Here with the answer is Brittany Shanka. She studies animal science at the University of Minnesota.

BRITTANY SHANKA: The sound that you're hearing is a cow chewing her cud. She'll eat first, and then she'll swallow that food, and that will go into the first compartment of her stomach. And then eventually, she'll spit that food back up and chew it up better and then swallow it so it goes into the other compartments of the stomach so it can be further digested.

MOLLY BLOOM: And what does that have to do with passing gas?

IRENE WEINHAGEN: I think what it does is because it's eating the food and then it goes into the compartment and then it just backs up and then eats it again and then that kind of has to do with the microbes.

MOLLY BLOOM: Mm-hmm.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Because then when it food backs up and eats it again, soon afterwards, it's going to be a fart.

[MOLLY LAUGHS]

A cow fart.

MOLLY BLOOM: To tell us is producer Marc Sanchez.

MARC SANCHEZ: Irene's guess is right on the money. Cows have microbes in their guts too. But their digestion works differently than ours. The gas cows pass is mostly in the form of methane. But what a lot of people don't know is how they let it out. About 93% of methane from cows is released through their mouths, not their backsides.

[COW MOOING]

Cows are part of a class of mammals called ruminants. Goats, sheep, bison, they're all ruminants too. And the thing that makes these animals alike is the part of their stomachs called the rumen. Some of you may have heard that cows have four stomachs. Technically, that's not true. Cows, like all ruminants, have one stomach with four compartments, or chambers. The rumen is the first chamber. And that's where all the gas comes from, through a process called fermentation.

When a cow eats, say, a big helping of grass or corn, there's hardly any chewing that goes on. They pretty much swallow everything whole. From there, it's off to the rumen. And that's where the microbes start to feast. This is what sets off fermentation. The leftovers of what the microbes don't use come out in the form of methane. I talked to Ermias Kebreab. He's a professor at UC Davis, and he studies cows and methane. And he broke down how cows break down their food.

ERMIAS KEBREAB: If you look at grass, they have cellulose. Cellulose is basically sugar or starch that's sort of joined together, and they have strong bonds that the microbes can attack and break down. They use that to grow themselves. So when they are breaking it down and using it to build their own bodies, they produce hydrogen.

MARC SANCHEZ: There are other types of microbes in the room and that feed off hydrogen. Those are called methanogens. And it's these methanogen microbes that give off, you guessed it, methane.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

A cow can't break down and ferment all its food at once. So what happens next might seem a little gross to you and me, but they sort of burp up a little ball of food called cud. Do you remember the mystery sound? That was a cow bringing her cud back into her mouth and chewing it up again.

That's what they do. And that's also how she releases the methane built up in her rumen. Several chews later, she swallows and sends her cud back down, and the microbes start the whole process again. This happens over and over until all the nutrients from that cud have been absorbed.

A healthy cow is pretty much constantly producing methane and releasing it into the atmosphere. And it turns out, all that methane can be problematic. Just like carbon dioxide and water vapor, methane is a greenhouse gas. Basically, a gas that can trap heat. You may have heard that excess greenhouse gases are contributing to climate change and heating up the Earth too quickly. But they're not all bad. We need greenhouse gases in moderation to stay warm.

ERMIAS KEBREAB: Without greenhouse gases, we won't be able to survive on Earth. Because the average temperature of Earth would be -18 degrees Centigrade if there was no greenhouse gas effect.

MARC SANCHEZ: For those of you playing in the US, that's just below 0 degrees Fahrenheit. Pretty chilly. But with all the cows and goats and cars and coal burning factories we rely on, we're producing too many greenhouse gases. Ermias is trying to figure out how to cut down the amount of methane cows give off. One way to do that is to change their diets,

ERMIAS KEBREAB: If you provide animals with easily degradable, less fibrous materials, then you would reduce the amount of methane that's produced as well. Very, very recently, there has been a development where a company has come up with a compound that would inhibit the production of methane, and they have shown that they can reduce it by about 30%.

MARC SANCHEZ: A 30% reduction in methane could be a huge breakthrough when it comes to cutting back the amount of greenhouse gases that are warming up the Earth. But like Ermias said, this is a brand new discovery, and there will need to be a lot of testing before this idea could have any major impact. Luckily, the farts that we humans produce are not a major contributor to the amount of greenhouse gases.

[COW MOOING]

So go ahead, enjoy those beans and broccoli.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Thanks, Marc.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Everyone passes gas.

MOLLY BLOOM: The gas is produced by the trillions of microbes living in our guts.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: And without these microorganisms, we wouldn't be able to digest food. And when we fart, it's actually the gas we're letting out.

MOLLY BLOOM: The smell of the gas the microbes produce depends on what we eat.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: And the sound the gas makes when it comes out is controlled by our bodies.

MOLLY BLOOM: Before we wrap up this episode, it's time to answer this question from Jasper.

JASPER KAVANAGH: Hi. My name is Jasper Kavanagh. I am nine years old, and from Chapel Hill. My question is, how does the Earth support really heavy buildings like the Empire State Building.

MOLLY BLOOM: It's time for our Moment of Um.

SUBJECTS: Um.

RONADH COX: The crust of the Earth is actually very thick. It's about 20 miles thick. My name is Ronadh Cox, and I'm a professor of geosciences at Williams College. If you imagine that the Earth is like an orange-- So you know when you hold an orange, it's got all the little lumpy bits on the skin? The mountain ranges on the surface of the Earth would be smaller than the lumps on the skin of the orange. So the Empire State Building looks really big to us and it looks really heavy, but compared to how big the Earth is and compared to how thick the crust of the Earth is, it's really not very big at all, and so the Earth doesn't even notice that it's there.

But of course, if you go to a place where you're not actually building on the bedrock of the Earth's crust but you are putting your building up on soft sediments, like dirt, mud, sand, then your building could sink into it. But it wouldn't be sinking into the crust, it would be sinking into the soft goo. It would be like instead of making a LEGO castle on a table, if you went and tried to build a LEGO castle on a soupy, gooey, swampy tub of mud, and the LEGO castle would sink into that. And that's why the Leaning Tower of Pisa is leaning, because it's not on solid rock and the ground that it was built on is settling underneath it.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: While you contemplate the bumps on the nearest orange, I'm going to hand out virtual high fives to the most recent group of kids to be added to the Brains Honor Roll.

[LISTING HONOR ROLL]

INTERVIEWER 3: (SINGING) Brains Honor Roll [INAUDIBLE]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

MOLLY BLOOM: That's it for this episode of Brains On.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: This episode was produced by Marc Sanchez, Sanden Totten, and Molly Bloom.

MOLLY BLOOM: Many thanks to Michael Sadowski, Laura Zabel, Levi Weinhagen, Sunpri Cower of UC Davis, Justin Sewell of UC San Francisco, Glenn R. Gibson of the University of Reading, James Buxbum of the University of Southern California, Evan Clark, Doug Rowe, Eric Wrangham, and Joe [? Feigs. ?]

IRENE WEINHAGEN: You can listen to past episodes at our website, brainson.org.

MOLLY BLOOM: Or in your favorite podcast app.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: You can find us on Instagram and Twitter.

MOLLY BLOOM: We're @Brains_On.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: And we're on Facebook too.

MOLLY BLOOM: And you can email us anytime at brainson at m, as in Minnesota, pr.org.

IRENE WEINHAGEN: Thanks for listening.

[FART SOUNDS]

Transcription services provided by 3Play Media.